Inhabitants of Oregon's Tidepools: Gumboot Chitons

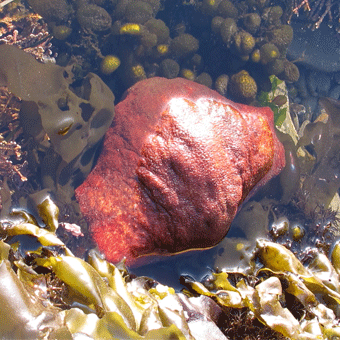

These slow-moving giants don’t look real.

Not speedy, not strong, not agile—gumboot chitons are just plain big and tough.

Like all chitons, gumboots are armored by eight plates over the back. But the plates of gumboot chitons are completely covered by the thick, skin-like girdle. Only a few predators, notably seastars and octopus, can make it through the tough skin: as long as it stays out of the sun, avoids the roughest surf, and keeps its less-armored side down, a gumboot might live for a couple of decades.

Less adept at hanging on than other chitons are, gumboot chitons are usually seen only in the lower intertidal areas, hiding in protected spots by day and grazing the algae off the rocks at night.

As tough as they are in their home, gumboot chitons won’t survive being taken away from their habitat: Please enjoy observing them where you find them.

Orange and yellow beneath, a deep slit all around the bottom separate the foot (in the center) from the outside edge; the gills of the chiton can be seen deep inside the slit.

About a quarter of all gumboot chitons are home to a kind of segmented worm that lives in the space with the gills, cleaning the gills and feeding on organic material.

Inhabitants of Oregon's Tidepools: Black Leather Chiton

How could something so humble-looking change the landscape?

Like many snails and some other mollusks, black leather chitons lick algae off the rocks with tongues that are studded with metal-tipped points. Over time, legions of chitons can literally wear down the rock. Black leather chitons live in places with heavy surf: How do they stay attached to the rock when big waves crash?

Like many snails and some other mollusks, black leather chitons lick algae off the rocks with tongues that are studded with metal-tipped points. Over time, legions of chitons can literally wear down the rock. Black leather chitons live in places with heavy surf: How do they stay attached to the rock when big waves crash?

The underside of the chiton has a deep slit a little inside the outer edge, where the gills are located, with a muscular foot in the center. The middle of this foot is pulled up while the outside edges seal, creating a suction that clamps the animal down. They move by relaxing the suction and making undulating waves against the rock with the foot. The black leather chiton’s low profile and slick surface probably also help resist the water’s pull.

Black leather chitons on the move are sometimes pried off the rock by black oystercatchers and eaten. People prying chitons off the rock can hurt them enough to kill them.

How do grazing molluscs feed?

Molluscs that graze to feed, such as most snails and chitons, scrape their food using paired, strap-shaped tongues that together are called the radula. Each strap is armed with many sharp, hard-tipped teeth; the pair of straps can look rather like an unzipped metal zipper.

Inhabitants of Oregon's Tidepools: Ribbed limpets

Home after a hard night’s work.

After a night of grazing algae off the rocks, ribbed limpets travel back to their homes: very shallow oval depressions in the rock, called home scars, which serve as parking spots. The home scar fits the bottom of the limpet’s shell precisely, helping the animal seal in the water when the limpet is clamped down on the rock during low tide. The slight depression may also make it harder for predators to gain entry.

Ribbed limpets, also called “finger limpets” because the ridges resemble fingers of a closed hand, are one of many limpets in Oregon’s rocky intertidal. You may find species of limpets that are flatter or steeper, or smoother. Move slowly and carefully for the best tidepooling—best for exploring and safest for you and for tidepool inhabitants.

Home is where you hang your…foot?

Some ribbed limpets make their home on rock, others take residence on the plates of gooseneck barnacles. Ribbed limpets on gooseneck barnacles are very well-camouflaged—can you find one?

Inhabitants of Oregon's Tidepools: Black Turban Snail

If you don’t see the door, the snail is gone—dead and likely eaten.

Turn a black turban snail over and you’ll see a circular, flat plate sealing the opening—in fact, you may get to watch the black snail close the door behind it as it pulls into its shell.These turban snails are called “black” because their bodies are black: the shells are charcoal gray. A bit rough in texture, patches of the outside of the shell often erode to purplish and the top of the spire usually wears down to the white mother-of-pearl beneath. Rather squat, with a short spire of rounded whorls, black turban snails can grow to about 1½” high and wide.

Turn a black turban snail over and you’ll see a circular, flat plate sealing the opening—in fact, you may get to watch the black snail close the door behind it as it pulls into its shell.These turban snails are called “black” because their bodies are black: the shells are charcoal gray. A bit rough in texture, patches of the outside of the shell often erode to purplish and the top of the spire usually wears down to the white mother-of-pearl beneath. Rather squat, with a short spire of rounded whorls, black turban snails can grow to about 1½” high and wide.

The closed door (also called an operculum) seals the opening to the shell, protecting the snail from drying out or from being eaten. Notice the concentric circles on the door? The door grows as the shell grows to accommodate the increasing size of the opening: the circles are the growth rings.

Even if the snail’s gone, the shell’s still of critical value in the tidepool: please leave them for other animals to use.

These turban snails are called “black” because their bodies are black: the shells are charcoal gray. A bit rough in texture, patches of the outside of the shell often erode to purplish and the top of the spire usually wears down to the white mother-of-pearl beneath. Rather squat, with a short spire of rounded whorls, black turban snails can grow to about 1½” high and wide.

Shells are valuable and are reused and recycled

Look closely at a shell—dead or live—and you may find barnacles, limpets, tube worms, or other animals or seaweeds attached. When the snail dies, hermit crabs and other animals may move in, as well. Eventually, even a sturdy shell will be broken down and the minerals will be dissolved in the water, later to be used by another animal to make a new shell.

Leaving shells on the beach keeps these precious resources available. Check out other tidepool etiquette tips.