Photo Gallery

Explore using the following slideshow to see a preview of some of the rocky shore photos available on Oregon State Parks' Flickr account.

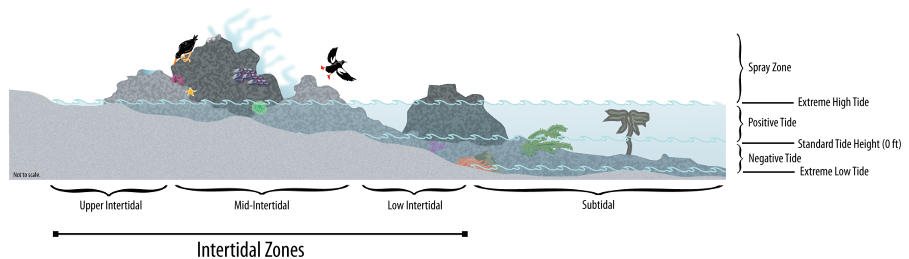

Tidal Zones

Intertidal Zonation

There are four commonly recognized tidal “zones” based on exposure during tidal periods, wave action and shoreline features. The presence or absence of water, temperature, wave action, variation in salinity (saltiness), exposure to light, and other factors determine what organisms are able to live happily in each zone. In general, physical factors, especially exposure to drying, limit how far up on shore an organism can live. An organism’s lower limit is often determined by competition or predators living in the lower zone.

Because a tidepool may hold water even during a low tide, a pool may provide suitable habitat for organisms that would normally be found in a lower zone. Giant green anemones and hermit crabs, for example, are generally found in the mid and low intertidal, but may be found in tidepools higher up.

Some organisms have a narrow range of tolerance for environmental factors and are found only in one zone, while others have a greater tolerance and are found in several zones.

Spray or Splash Zone

This area extends from the highest reach of spray and storm waves to the average height of the high tides. It is usually dry, and relatively few types of organisms can live here. Species found in the splash zone might include: small barnacles, periwinkles and ribbed limpets.

Upper or High Intertidal Zone

This zone includes the area from the average high tide to just below the average sea level (i.e., covered only by the highest tides). Species found in the high intertidal zone might include: acorn barnacles, hermit crabs, shore crabs, black turban snails, aggregating anemones, sea lettuce, and rockweeds.

Mid Intertidal Zone

This zone extends from just below average sea level to the upper limit of the average lowest tides (i.e., it is exposed at low tides-usually twice a day). In a healthy intertidal area, this zone is rich both in diversity and numbers of organisms. There is generally a dense cover of algae, providing food and shelter for many animals. Species found in the middle intertidal zone might include: California mussels, giant green anemone, ochre sea star, black leather chitons, gooseneck barnacles, coralline algae, sea palms, and sponges.

Low Intertidal Zone

This zone is exposed to the air only at the lowest tides. Species found in the lower intertidal zone might include: gumboot chiton, ochre sea star, kelp crabs, blue top snail, purple sea urchin, feather boa kelp, nudibranchs and sponges.

Subtidal

Subtidal organisms that you are likely to encounter (sometimes washed up on the beach) include bull kelp, many bottom-dwelling invertebrates, and various fish. Sunflower sea stars tend to occur subtidally but occasionally will come up higher into the low tide zone.

Other visitors (e.g., marine birds and mammals)

Many kinds of birds are likely to been seen in or near the intertidal area, including various gulls, black oystercatchers, cormorants, pigeon guillemots, common murres and brown pelicans. Likewise, you may see mammals such as seals, sea lions, and whales. Please note, if you see a marine mammal on the beach, leave it alone. Marine mammals will often come ashore to rest and can be aggressive if they feel threatened.

Descriptors of the zones are approximations and may vary due to the shape of the shoreline, latitude, and other factors. Similarly, plants and animals don’t always stay in the zones where they are most commonly found.

Tidepool on Oregon's Central Coast

Credit: This text on intertidal zonation was slightly modified from California State Parks' "Guide to the Side of the Sea" with permission. The full teacher's guide for field trips to rocky intertidal areas can be downloaded from the California State Parks website.

Major Communities of Oregon Tidepools

Patterns of Intertidal Life

The greatest of many challenges for marine organisms living in the intertidal is the exposure to air and its related difficulties. Different organisms have different tolerances for the challenges; they tend to live with others of similar tolerances, forming communities. (A few active organisms, such as sculpins and hermit crabs, may move from community to community with the tide.)

Bounded primarily by tide level, these communities often form visible zones on the shore. These zones are pretty reliable, but not absolute: they may vary by local conditions, such as the shape of the land and the force of the currents or surf.

Exposure to sun, surf, and sand can also greatly impact where intertidal organisms live. Protected spots in crevasses, holes, nooks, under rocks and under other inhabitants are high-value real estate that harbors more—and different—life than less protected areas do.

Neighbors also affect communities: Some members of a community may provide shelter for other, less-resilient members—California mussels provide shelter for a large variety of organisms that live beneath them, and purple sea urchins create pits that shelter other community members, for examples. Communities can be affected by those nearby. For example, the bottom boundary of mussel beds is delineated by the upper limits of the ochre sea stars that feed on them.

What do you notice about the community patterns on the shore you’re exploring?

How do these patterns form?

The tide and currents can transport larvae to all parts of the intertidal, with many settling and attaching where they eventually won’t survive. Although you may see a youngster “out of place” where it will eventually die, most of the intertidal organisms you find are those remaining where they’re adapted to survive over the long run, through years of tides and storms. Keystone species, such as ochre sea stars, can set the stage for other community members, including California mussels.